Let Me Entertain You: An Origin Story and a Hot Take

The Intelligent Showmosexual's Guide to Theatergoing and Ticket-buying With a Key to the Pictures

Exposition

Friends and family members have encouraged me to create some sort of record of my theatergoing experiences for so long that one of my earliest pieces—tentatively titled “Give Me Libertines or Give Me Death,” and focused on how Michael John LaChuisa’s scores for The Wild Party and Marie Christine and Shaun Davey and Richard Nelson’s for James Joyce’s The Dead were all more deserving of the Tony than Elton John and Tim Rice’s for Aida—was rejected by my high school literary magazine as being too niche. The popularity of potential outlets, ranging from live journals to vlogs, would wax and wane, and I never got around to compiling my thoughts…partially because I was still entertaining dreams of a career in theatre and didn’t want to alienate anyone, and partially because I didn’t think the world needed yet another homosexual opining on an arguably elitist and perpetually dying artform. Now, however, in an era of heightened toxic masculinity where Wicked is breaking box office records over twenty years into its run, I think that’s EXACTLY what we need.

Furthermore, and despite the best efforts of Dr. Ali Vafa and Mario Badescu, I’m aging. Wrangling my reactions into something coherent and shareable seems like a great way to keep my mind sharp and my memories vividly encoded. So, welcome to my experiment in unleashing not just the homosexual, but the full-on SHOWMOSEXUAL: the superfan who somehow performed professionally for a decade (and earned an MFA in Acting and a Masters in Theatre Education) without ever losing a childlike enthusiasm for theatergoing so extreme that he still hoards “slime tutorials,” in formats from VHS to VOB; catalogues the shows he sees in an Excel spreadsheet; and saves all his Playbills and ticket stubs in miniature binders. Brace yourself for some critique, some memoir, and some celebration of all the qualities that got me mercilessly mocked in middle school.

Inciting Incident

When I was only eight, the 1989 revival of Gypsy (to this date, its only production to take a “top” prize at the Tonys where it won Best Revival of a Musical) became my first Broadway show and ignited a lifelong passion. It’s impossible to describe my excitement. I had loved seeing my older siblings in school plays, but, as soon as I entered the St. James Theater, the plush seats and ornate chandeliers promised an experience of an entirely different, far more thrilling scale. Moreover, my mother had taken my sister Hope to see the production with Tyne Daly earlier in its run. I’d spent months pouring over her Playbill, which at that time included some poor-quality production photos, imagining what they’d seen that elicited such raves, and now I was about to find out for myself—with one important difference.

Linda Lavin had recently taken over for Tyne Daly. Reruns of Alice were my version of chicken soup whenever I was home sick from school, and I couldn’t believe I was going to be sharing oxygen with La Hyatt herself. This was the first time I’d ever been in the same room as a celebrity. Lavin’s presence, and my preexisting knowledge of who she was, immediately embedded an understanding in me that one aspect of theatre that makes it so special is that you’re in the same space as its creators as they’re creating it.

That being said, I almost instantly forgot about Lavin’s sitcom character from the moment she walked through the aisle, commanding, “Sing out, Louise!” Her Rose was a tireless fighter and I was enthralled watching her go to battle. It felt like I started holding my breath at “Some People” and didn’t exhale until the revelation that she was determined to make Louise a star caused me to gasp near the end of the first act. I didn’t yet have the language to articulate it, but watching that performance was also the moment when I came to see my own parents as people—with their own hopes and dreams and disappointments—rather than gods. Seeing Gypsy was life-changing in countless ways.

It was also my third Broadway show because I incessantly badgered my parents into taking me back to see it when it was remounted with Daly for a return engagement. (Thus began another lifelong obsession: seeing different greats tackle the same roles.) I saw the subsequent Broadway revivals with Bernadette Peters and Patti LuPone five and three times respectively, and traveled to London to catch Imelda Staunton helming its first revival on the West End. I even got to direct it in college where, much to my own self-satisfaction, an article in the university paper honed in on my “color-blind” casting as a contrast to our theatre department’s more homogenous aesthetic. It therefore feels almost inevitable that an endeavor like this one would begin with a production of Gypsy, especially its first Broadway production to cast Black performers in its lead roles.

Action

The revival of Gypsy currently playing at the Majestic Theatre on Broadway—which I’ve crucially now seen twice—is directed by George C. Wolfe, who has not only been instrumental in creating some of contemporary theatre’s richest explorations of race (including Caroline, or Change, which I believe is the greatest musical of the 21st century) but also helmed the production of The Wild Party that my high school emphatically did not want to read about. And, of course, his star is not just any Broadway star; it’s Audra McDonald, the highly deserving record holder for most Tonys as an actor and the only performer to win a Tony in all four acting categories. With such a pedigree behind it, I headed into a second-week preview with reasonably high expectations. At the same time, I also had serious reservations. Originally written for Ethel Merman, Rose’s songs epitomize traditional Broadway belting, and McDonald is a classically trained soprano. I was hoping she’d surprise me, as she did with her revelatory turn as Billie Holiday in Lady Day at Emerson's Bar & Grill, but I also could not forget her performance as Deena Jones in Dreamgirls…where she sounded more like Leontyne Price singing the music of the Supremes than Diana Ross.

I’m going to focus most of my reaction to the production on the second performance I attended, which was after its official opening, but it seems too significant to omit that, at the preview performance I saw, I was indeed surprised: surprised that McDonald acted the part even better than I expected, which is saying something, and sang it even worse, which is also saying something. I may have never heard such a gifted musician struggle as much with their singing as she did at that preview. I sincerely hope it’s not a harbinger of inconsistencies to come, but given the scrutiny incurred and havoc—pun intended—wreaked by the score on more natural belters’ voices, I think anyone headed into production, especially if they’re fond of its music, should manage their expectations as to how its iconic anthems are going to be sung.

And yet, even at that early preview and in spite of a few seriously questionable choices, this is the best Gypsy I’ve seen since Daly’s return to the role in 1991. In many ways, it’s a shockingly conventional production, but that’s also one of its greatest strengths. Wolfe trusts the story and he trusts his storytellers. Rather than emphasize a concept or demonstrate his own cleverness through unusual staging, he handles the text with a light touch that allows us to connect with the various characters’ needs for more—more attention, more love, more fame, more money, more opportunity.

Rose’s needs feel particularly urgent and honest, just as they should. In ways that Peters and especially LuPone did not, McDonald disappears into the role. While she is naturally elegant and exudes self-assurance, her Rose is unrefined and desperate to rise above her station. What’s even rarer is that McDonald conveys to great effect the fierce love she has for her daughters. It makes key plot developments immeasurably more poignant, but even brings rich meaning to smaller moments, like when she asks how she and Louise are supposed to eat if June departs their act for drama school and the throwaway joke about her eating dog food so the girls can have Chinese food after a performance. If some of McDonald’s choices as a singer feel necessitated by the nature—and limitations—of her instrument, they are more than offset by her riveting choices as an actor, which feel incredibly thoughtful and grounded in reality while still consistently dynamic.

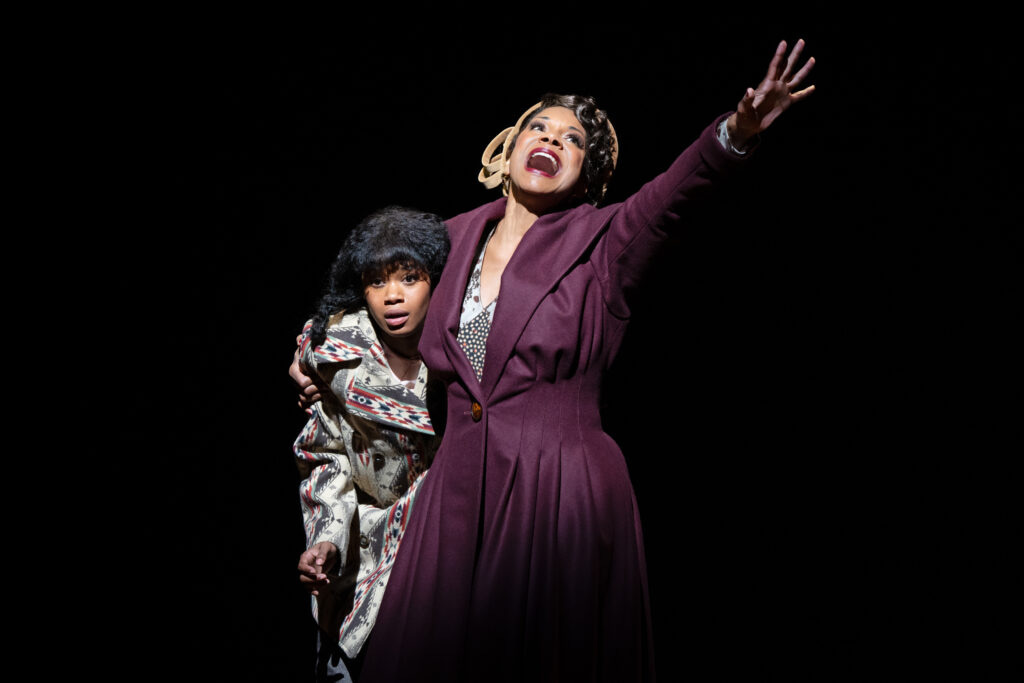

When Wolfe does add directorial flourishes, they are, for the most part, thoroughly impactful. Many of the most thought-provoking are indeed around race: as Rose and Herbie (Danny Burstein) try to convince a theatre manager that her act—which is filled with Black performers—can inject new life into his dying vaudeville venue, we simultaneously see a stodgy Fred and Adele act perform antiquated choreography on his “stage”; as time passes and the act moves up on the circuit, Rose replaces the Black dancers with white ones…all except Louise who’s relegated to waving a flag in front of her face in the background; colorism is subtly explored with the casting of a light-skinned June (Jordan Tyson) and a dark-skinned Louise (Joy Woods), whose hair Rose is constant fussing over. It’s disappointing, then, that the staging does little to explore the connotations of Rose and Herbie’s interracial relationship, especially in light of the characters’ frequent debates around marriage, which would have been taking placing decades before Loving v. Virginia. It’s as if Wolfe opted for a color conscious treatment of the text in every way but in response to Rose and Herbie. A friend of a friend who worked on the production tells me that voluminous research was done to support the idea that Rose is “trying to legitimize herself” by latching onto a white man, but it simply does not read.

To be honest, though, casting Burstein may have sealed the production’s fate that their relationship would be handled, or at least play, more traditionally. Burstein is a fine journeyman actor who turns in a credible performance. He admirably holds his own against McDonald, but he offers no new or exciting point-of-view on the character. As I bitchily quipped to a friend, “Burstein was better in 1990 when he was Jonathan Hadary.” As another friend said, Burstein may not have played the role before, but it feels like a performance we’ve seen before. And before anyone says the role does not allow for that, I would encourage them to check out John Dossett’s work in the Mendes production. Still, the fact that Burstein is the production’s biggest liability (or at least second to McDonald’s vocals) speaks to its overall strength.

The other principals fare far better, especially Tyson, who is a revelation as June. In part because of some additional opportunities Wolfe gives her, she makes more of the role than any of the very respectable other actresses I’ve seen play it. Her longing for a better life is just as palpable as Rose’s. It’s also the first time that we, the audience, can see the potential to be a great actress in her that Grandzinger sees, which makes her decision to run away from Rose all the more justifiable.

Woods, although very strong, is hindered by a few of Wolfe and choreographer Camille A. Brown’s most questionable choices, particularly during the climactic strip sequence where she transitions from diffident little Louise to Gypsy Rose Lee, Queen of the Striptease. For some maddening reason, they’ve cut the pivotal line when she first introduces herself as Gypsy Rose Lee, depriving Woods of the moment to realize and then relish her new identity. An extended “Garden of Eden” strip is clearly supposed to be a showstopper, but looks so tacky (other than Woods’s knockout styling) and anachronistic, my inner voice started riffing on one of my favorite laugh lines in Paul Verhoeven’s cult classic Showgirls: “We could've brought anyone into this show. Latoya, Suzanne, [Josephine Baker,] you name it.” However, even if denied the right opportunities to connect the dots, Woods still delivers a highly satisfying performance and effectively captures Louise’s tender insecurities and Gypsy’s vulpine bravado. And, for the record, most of Brown’s work, especially in transitional scenes, is so damn good, I was shocked to realize that I was not missing the brilliant original choreography of Jerome Robbins.

In featured roles, the endlessly inventive comic prowess of Mylinda Hull, big voice of Lili Thomas, and hilarious lack of self-consciousness displayed by daffy Lesli Margherita combine for a shows-topping “Ya Gotta Get a Gimmick”; Kevin Caszlo’s dancing in “All I Need Is the Girl” brought a genuine smile to my face (even if I found myself missing the virility and grace that Tony Yazbeck brought to the role in 2009, effortlessly evoking a young Gene Kelly); and, in a bit of luxury casting for the small role of Agnes, Brittney Johnson charms as much as you would expect a former Galinda to.

Ultimately, regardless of how impressive its supporting cast may be, the performance of the actress playing Rose most decides the success of a production of Gypsy. And this one stuns, truly solidifying claims that Gypsy is the best Broadway musical ever written because McDonald is in full bloom. Disabuse yourself of the hope that you’ll hear this score belted in the way you’re accustomed to hearing it, and your experience will be more than swell; it will be great.

a guide to ticket-buying

For Dec. 6, 2024: $249 / Orch. K 109 (special price/seating for American Express cardholders)…a perfect location, particularly for someone on the petite side—AS YOU KNOW I AM—because it’s the first raked row in the orchestra

For Jan. 3, 2025: $89 / Orch. U 27 (purchased at TKTS)…decent view, especially for the price, but having recently had knee surgery, I was told I would not need to walk steps to get to this seat and I absolutely did

a key to the pictures

If you want to consume Gypsy on film:

The 1962 feature film directed by Mervyn LeRoy has its defenders, probably because Natalie Wood is so compelling in the title role, but I find it excruciatingly tedious. Out of respect for her work in His Girl Friday, The Women, and Auntie Mame, I’ll say nothing about Rosalind Russell’s performance as Rose.

The 1993 telefilm with Bette Midler as Rose is probably your best bet, but some people find her “too Bette” and the adaptation too “stagey.” I like how faithful it is to the source material and, while I would never describe Midler as a chameleon, find it to be a good match between actress and character.

In 2016, Lonny Price directed a live capture of the West End revival with Imelda Staunton who seems to have very intentionally chosen not to recalibrate her performance for the camera. If you accept that you’re watching a “big” interpretation intended for the stage—and that nearly everyone in the cast is about ten years too old for their characters—there’s a lot to admire in the production. Staunton’s unapologetically ruthless take on her character will surely turn some viewers off, but I suspect it’s the closest experience contemporary audiences can have to what audiences in 1959 must have felt when they were first introduced to Rose by Merman.

I didn't experience this production, but can can't help but think there is something kind of brilliant in McDonald's inability to belt the score. Success as a performer eludes the character, and feeling the actress/character fall short of the musical mark may layer in some context about why she has to pursue the dream through her children.

I re-read this after seeing the show (which I thoroughly loved), and it added even more depth to my experience of it. Thank you for your words, your enthusiasm, your nuanced take, and for how you see.