As If We Never Said Goodbye: My Long History Cruising Sunset Blvd. (the musical, you pervs)

The Intelligent Showmosexual's Guide to Theatergoing and Ticket-buying With a Key to the Pictures

An Overture

Introductory notes before a review of the current revival

“Let me take you back…”

I know it hurts my snob cred., but I fucking love Sunset Blvd. and I always have.

Like the musical I used to start this endeavor (Gypsy), Sunset Blvd. is a show with which I have a long history. As an adolescent showmosexual growing up outside of New York City, long before YouTube or Instagram and even Rosie O’Donnell bringing Broadway back to daytime television with her talk show, the Tony Awards were often my best window into contemporary theatre. (This is a key reason why they need to bring back the performance clips from straight plays—watch Linda Lavin in Brighton Beach Memoirs or Julyana Soelistyo in Golden Child for a sense of how well they can work when presented straightforwardly.) I had a VHS tape with the ceremony where Angela Lansbury and Bea Arthur recreated “Bosom Buddies” that I watched so obsessively, I could do the choreography. As I became more and more of a theatre kid, the Tonys became my favorite night of the year, a sort of gay Super Bowl, though I never threw parties to watch it because I was too afraid people would talk.

I was in middle school the year the original production of Sunset Blvd. opened on Broadway. Having never seen the movie or gotten much into the Andrew Lloyd Webber musicals that were popular at the time (Phantom of the Opera, Cats, Joseph…), I’d paid little attention to it, though my ears perked up when I heard Glenn Close was starring in it. After all, like any other adolescent boy, I loved Fatal Attraction and The Big Chill. Nevertheless, I was so deep into a fixation with Kander and Ebb’s Kiss of the Spider Woman, I hadn’t even bothered to check out a Sunset Blvd. cast recording at a Borders Listening Station.

Then came the night of the Tonys. From the moment Close stepped onstage to perform “As If We Never Said Goodbye,” I was transfixed. The desperation, joy, vulnerability, and greed in her Norma’s eyes as she reclaimed the spotlight were a master class. I immediately had to learn more about the musical that encased them.

Glenn Close performs "As If We Never Said Goodbye" from Sunset Blvd. at the 1995 Tony AwardsWithin weeks, I became obsessed with Sunset. It’s a stereotype that gay men love a tragic diva, but it’s a stereotype that is often true, at least of me, and Sunset gave me my first. On one hand, it’s hilarious to think that I, a seventh-grade boy trapped in suburbia, related to Norma Desmond so intensely; on the other, I think it speaks to the empathy the story and score engender, and just how damn overlooked and underestimated I felt. Maybe it’s these feelings that have always made Sunset Blvd., even before it was musicalized, such a dog-whistle for gay men.

I bought every cast recording I could and tracked down audio bootlegs of different performances (though I refused to watch a video until I’d seen it live). In almost no time at all, my childhood best friend and I had the entire show memorized. We would “play Sunset.” And I don’t mean listen to the album—we would perform the show in its near entirety, skipping the ensemble sequences and begrudgingly taking turns playing Norma. (I’ll let you surmise his sexual orientation.)

My fascination would only intensify as I learned about the backstage drama that surrounded it: Patti LuPone’s very public dismissal; the abrupt closure of the Los Angeles production when it was deemed Faye Dunaway could not sing (or, I suspect more importantly, sell) it; the falsification of box office records when Close went on vacation to suggest the musical was not dependent on her star power; and the scathing letter she wrote when she discovered the fraud, which mysteriously found its way to the press. I read and reread the handsome coffee table book published after its opening in London countless times, spellbound by the gap between what everyone involved had said about the show publicly and what the ensuing months would reveal they had really felt.

After so much anticipation, you’d think that when I finally saw the show, it could not possibly have lived up to my expectations, yet I loved it even more. Betty Buckley had assumed the role of Norma and gave a performance that was as surprising as it was thrilling. The sheer force of her belt induced goosebumps, but what made her performance truly haunting was how its superhuman strength was paired with a characterization defined by its woundedness. Haughty and majestic as her Norma was, she also personified the damage the entertainment industry can wreak. Buckley’s acting showed us a Norma who was a raw, exposed nerve while her singing showed us the untapped power that was still in her. Has any other actress ever succeeded in making melancholy theatrical?!

A pretty decent capture of Betty Buckley's first scene as NormaThe rest of the cast was also fantastic—Alan Campbell effortlessly grounded the production as Joe Gillis, George Hearn stole the audience’s heart with his tragic devotion and flawless vocals as Max, and Alice Ripley brought real backbone to the potentially one-dimensional ingenue role of Betty—but decades of talk about the original production’s unparalleled visuals, which were genuinely exquisite (those costumes! that mansion!), have left director Trevor Nunn’s contributions undeservedly out of the conversation. He masterfully found realism in spectacle and musical melodrama, and his juxtaposition of Norma and her closeup made for an indelible closing image.

Rather than leave me sated, seeing and loving the production so much only made me want to go back again. After my parents resisted my pleas, I decided to take matters into my own hands: I organized a field trip for the cast and crew of my middle school musical to see it at the end of the school year. (When my former music teacher retired a few years ago, he told me it became a tradition that continued as long as he was at the school, and I thought, “Wow, this is like the theatre queen equivalent of the butterfly effect.”) In a particularly surreal coincidence, when my classmates and I sat down at the theater and opened our Playbills, we discovered that it included a letter I’d written with a question about Sunset. My peers thought I’d somehow planned it, but for me it felt like a celestial confluence of events proving that I shared a special connection with the musical.

During Sunset’s original run and subsequent tours, I caught the Normas of Karen Mason, Elaine Paige, Linda Balgord, and Petula Clark. Close, though, seemed like she’d always be the one who got away, my powder-white whale. I resigned myself to not understanding what special magic her performance held because, as great as the Tonys number was, it certainly did not translate to the cast album, on which she’s often painful to listen to.

So when it was announced that she’d be starring in a semi-staged concert revival at the English National Opera for one month only in 2016, I pounced. I scraped together the little money I could find as a first-year teacher and bought tickets to two performances—a Saturday and a Monday evening, reasoning that if she was sick and missed the former, she’d have their dark day to recover and go on at the latter. My friends and family told me I was crazy. “It’s one month,” they said, “she’s not going to miss any performances!”

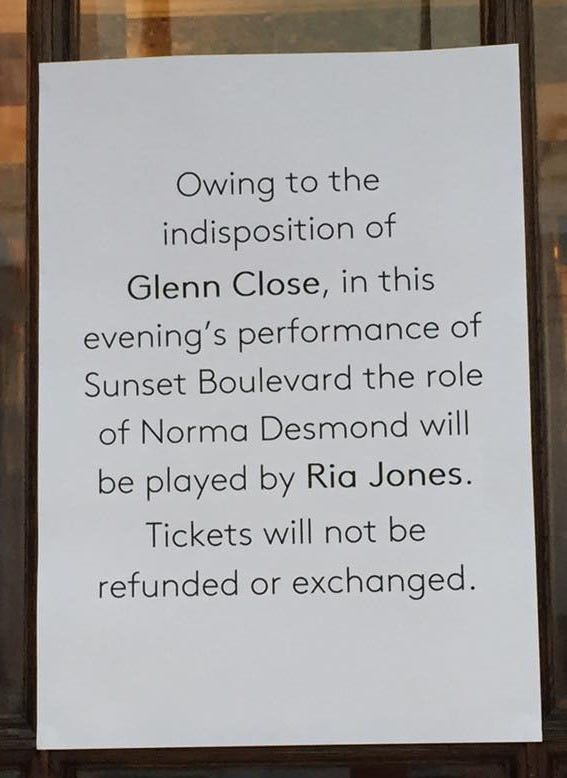

Well, lo and behold!, as I headed to the airport on Friday, news broke that Close had fallen ill and her standby, Ria Jones (who performed as Norma at the very first public reading of Sunset before even LuPone came aboard), would be going on as Norma. I tried to assuage my panic by reminding myself of my two-ticket-purchase-insurance-policy, but when I arrived at the show on Saturday night and signage everywhere indicated that Close was out again, my plan started to feel more like wishful thinking. Despite the performance being sold out, and the English National Opera refusing to make any exchanges or returns, there were scores of empty seats everywhere. When a small, mild-mannered man who looked more like a marionette than a person came out to make the understudy announcement, the audience actually booed. I was shocked. Weren’t the English supposed to be more polite than Americans?!

Jones was great and quickly won over all those that decided not to eat their ticket purchase that night, but it was with immense relief that I discovered, on Monday night, Close would be going on. The same meek man stepped out onstage before the overture began, and I felt a surge of anxiety. Was there a last-minute change of plans? No, instead, he informed us, that “Ms. Close is going on against doctor’s orders” and asked that we be…understanding. Despite some very shaky vocals, the preemptive apology was not necessary: that night at the ENO, Close gave the best performance I’ve ever seen in anything anywhere. I’d finally experienced what the cast album could not capture, and the twenty-year wait had been worth it.

Imagine my surprise just a few months later when it was announced that the ENO production would be transferring to Broadway. The, shall we say?, “bosom buddies” in my friend group bubbled with schadenfreude. “Are you so upset that you spent all that money to go to London when Sunset is coming here?” And the answer was, “Of course not.” I was overjoyed I’d be able to see her performance again. Which I did. Multiple times. Including at the first preview, closing, a Valentine’s Day celebration with my then partner, and one particularly special experience that I’ll save for the very end of this piece.

Despite raves for Close, including a love letter in the NY Times that declared Norma to be now as much her role as Gloria Swanson’s, the revival was not well received. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I thought it was terrific. Director Lonny Price did a fantastic job of telling the story with significantly fewer resources than Nunn, navigating the piece’s secondary romance with particularly intelligent expertise. Michael Xavier’s Joe was unbelievably sexy, perfectly striking the balance between snark and disillusionment, and sensitivity and charm. Siobhan Dillon was a perfect Betty, infusing the role with the intelligence and determination that a career woman in the late 1940s would have had to possess without losing any softness or romantic charm. (As Max, Fred Johanson was also there.) When the production was completely snubbed by the Tonys, it felt as if this Sunset was being punished for the first production’s lack-of-competition on the awards circuit in the 90s.

In an especially powerful full-circle moment, my most memorable experience with Price’s revival came when I organized yet another middle school fieldtrip to see Sunset Blvd.—only this time, as the teacher. Like any responsible educator, I made sure to sit myself next to the student who most needed monitoring during the performance. We’ll call her “Coco.” Coco was a ferociously talented and incredibly bright eighth-grader who also had a tendency to act out. The students on the trip were drawn from the casts of school productions I’d directed, including one of Once on This Island in which she’d played Asaka. Although the experience had created a sort of bond between us, I still never knew which Coco we were going to get, and I wanted to make sure she wasn’t disruptive to the other patrons at the theater.

Initially, she had me worried. She seemed bored and disinterested in the production, qualities that can often lead adolescents into trouble. But she started sitting up a little taller as Norma’s erratic nature became clearer. As the drama intensified near the close of the first act—with the rapid developments of Norma throwing herself at Joe, attempting suicide after his rejection, and then presumably consummating their relationship in the face of his guilt—Coco was fully paying attention. “It’s alright,” she said guardedly at intermission.

By the time Joe catches Norma calling Betty, all my students, including Coco, were invested. In one especially fascinating moment that speaks to the collective experience of theatergoing and group mind of an audience, they all had an audible reaction to Joe breezing past Norma as she thanks him for rejecting Betty. (Unbelievable but true: when I posted about the field trip on Facebook that night, a former classmate who’d gone on the field trip with me back in the 90s replied, “I was there too! Were your students the ones who all reacted when Joe ignored Norma near the end?”) After Norma made her final descent down her staircase in madness, my students went wild.

As the audience applauded, Coco grabbed my arm to get my attention. She pointed to tears streaming down her face. “Mr. V.!” she exclaimed. “Mr. V.! I’m crying for a crazy person!”

I laughed and said, “I see.”

“No,” she continued, frustrated I didn’t get it. “I’m crying for a crazy person, and…THAT’S…THEATRE!”

She’s damn right it is.

👏👏👏 Bravo.

For neither the first nor the last time, I lament that we did not know each other as kids. I sang “With One Look” in multiple talent shows in 7th grade, including one where my grandma made me my own Norma costume. I have very strong opinions about the recordings — my favorite might be the Diahann Carroll/Toronto because Rex Smith is a weirdly perfect Joe (and sings it really well) — and the movie too is very important to me. (I went to Nancy Olson’s book signing last year — come for the Sunset stories, stay for the “what it’s like to be married to Alan Jay Lerner” stories…) Anyway, thrilled you’re doing this 💖